By Geeta Dayal

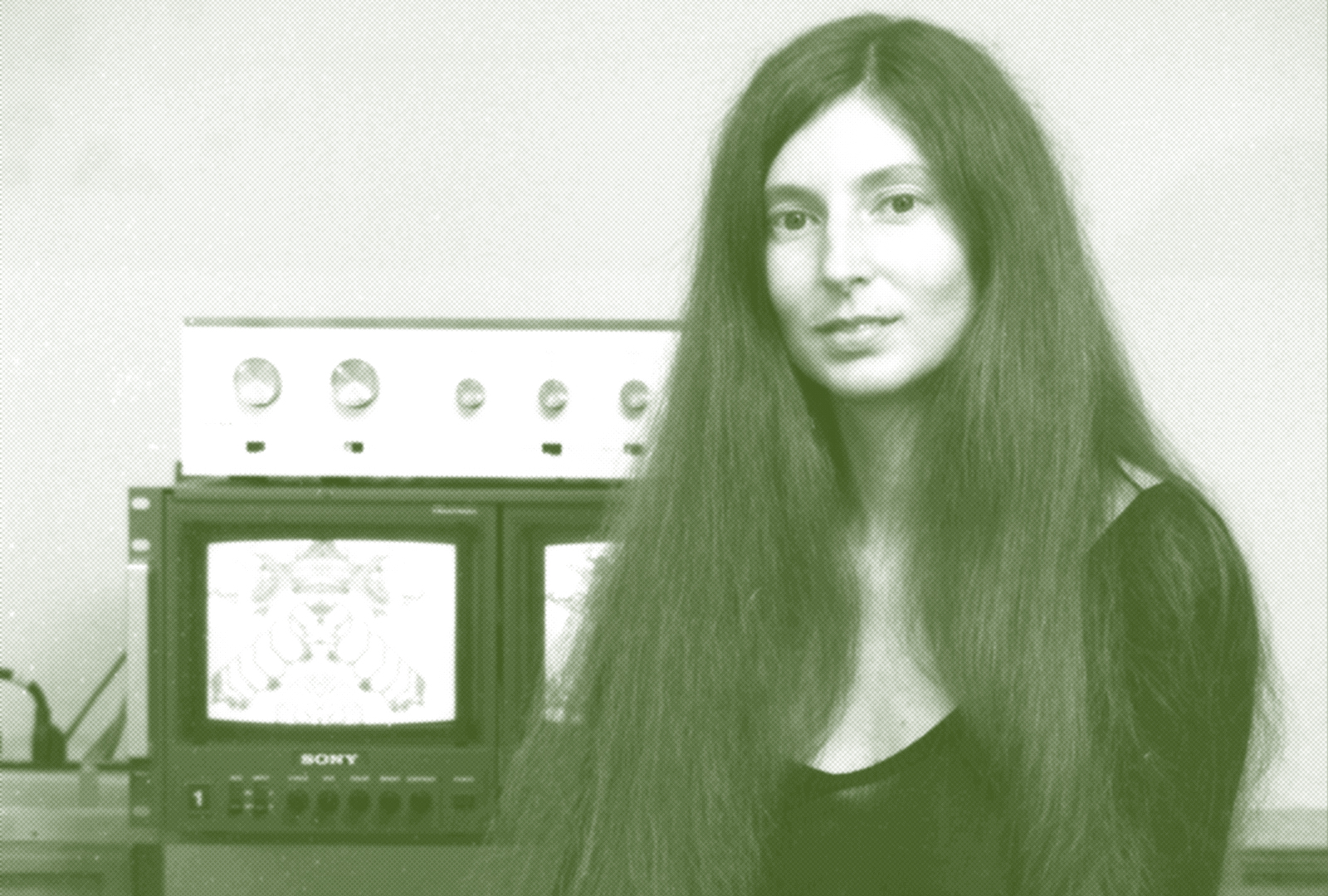

Maggi Payne: A Nexus For The Next

There’s still a lot of territory to explore

“There’s still a lot of territory to explore,” says Maggi Payne, now 77. Payne is a composer, flutist, and sound engineer known for her imaginative work in electroacoustic and electronic music. She has explored sound over a long and varied career, including over fifty years as a student, artist, and professor at Mills College in Oakland.

She developed a strong interest in music as a child growing up in Texas in the 1950s. When she was nine, she heard a flute and became enchanted by the timbre. She began flute lessons with great excitement. “It was such a versatile instrument,” she said. “I just immediately fell in love with it.”

Her father was a doctor who was interested in technology. “When I was ten, my father bought me a Webcor model reel to reel tape recorder,” she remembers. “When he bought me this tape machine, I recorded everything possible and slowed things down and [sped] up. I loved the technology. I could record one part of a duet and then play live . . . I was playing duets with myself.”

Her interest in the possibilities of tape deepened. “A few years later, my father bought me a very old Sony tape machine with multiple tape speeds and sound on sound so I could overdub,” she says. She continued flute, exploring extended techniques, and studied classical and contemporary music. By the time she was a teenager, she was immersing herself in 20th century music by the likes of Edgard Varèse and Luciano Berio.

Contemporary music in the 1960s was a very male-dominated world, but Payne had great support from her parents and teachers. “Even when I was sixteen years old, it never occurred to me that as a girl, as a woman, I couldn't be a recording engineer,” she said. “It never occurred to me that I couldn't be a composer.”

She continued her education at Northwestern and then went to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, which had a wildly innovative music department with faculty including computer music pioneers Lejaren Hiller, Herbert Brün and Salvatore Martirano. John Cage premiered his multimedia extravaganza HPSCHD at Illinois in 1969 — an ambitious work that included numerous harpsichords, projectors, and tapes of computer-generated sounds — in collaboration with Hiller. Robert Ashley came to campus to perform his powerful, noisy piece Wolfman.

She recalled having lunch with John Cage as a student in Illinois. “He just had a wicked sense of humor,” she says. As he was cleaning mushrooms to put into an omelet he was telling her a story that the night before he had accidentally poisoned people with mushrooms. She wondered for a moment if she should eat the mushrooms. Everything turned out fine, and she and Cage got along famously.

At Illinois, she was able to gain access to gear beyond tape machines, studying with Martirano, James Beauchamp, an acoustics expert, and Gordon Mumma, a legend of electronic music who was in residence at Illinois that year. Mumma advised her to continue her studies with Ashley at Mills College. In 1970, she headed to Oakland, California to study with Ashley in the newly established degree program in electronic music and recording media.

She was enthralled by the beauty of Northern California’s lush landscapes when she arrived. “Everything was so beautiful,” she said. “The ocean and waterways and amazing trees … I came from the desert, you know.” The Bay Area had become a centerpiece for the hippie counterculture, with the Summer of Love and local bands like the Grateful Dead, Sly & the Family Stone, and Jefferson Airplane achieving national fame. And the San Francisco Tape Music Center – conceived in 1960 by Ramon Sender, Pauline Oliveros, and Morton Subotnick – was pushing the boundaries of electronic music, hosting historic early performances by composers including Steve Reich and Terry Riley. “I was drawn to the West Coast because of its exquisite beauty, the free spiritedness and welcoming of experimentation in art, music, film, video, dance, literature, poetry, electronics, lifestyles, and more,” Payne says.

It was as if experimentation permeated the very air that we breathed.

The 1960s had drawn to an end, but in the 1970s, across the bridge in Oakland, sounds were percolating at Mills College that continued the San Francisco Tape Music Center ethos — abstract, non-commercial sounds made with synthesizers and other devices. Pioneering Bay Area inventors like Don Buchla, who had worked with the Tape Music Center, designed exciting new electronic musical instruments which were pushed to their limits at Mills. Less than an hour’s drive away, in Silicon Valley, the personal computer revolution was taking hold. “The proximity to Silicon Valley stimulated the community in interesting ways,” Payne says. “Many of us built our own circuits in lieu of pricey store bought circuits.” They bought parts and gear for their handmade music from the same electronics surplus stores frequented by Silicon Valley pioneers.

Ashley led the nascent Mills graduate music program with his inexhaustible energy and undeniable charisma. “Everyone loved him,” Payne said. “He was a brilliant guy. I can't say it enough about him.” Many other noteworthy composers were on the faculty in the 1970s, including David Behrman and Terry Riley. Mills, she remembers, was a true community. “It was just like a big family,” she said. “It was really quite extraordinary. And it was not competitive.”

She explored electroacoustic and electronic music, and intensified her investigations of extended flute techniques, such as multiphonics, humming, flutter tongue, and whistle tones. In 1973, she made a piece called “Hum.” “That one was all about humming, obviously, but also a lot of spatialization [was] going on there,” she says. The piece used two microphones and she moved between the two. “I could get spatialization going as I was playing. So I would be blowing wind, you know, into the mics and moving my body . . . changing the sound.” She also collaborated with other composers, contributing e-flute parts to records including Behrman’s 1977 album On the Other Ocean and Joanna Brouk’s 1981 album Healing Music.

Payne also makes electroacoustic music with field recordings. “There’s something about the sounds in the world that have a really intriguing complexity,” she says. She treats the sounds in various ways. “At times I do a lot of electronic music, but I also do a lot of music using natural sounds, but they are easily processed beyond recognition.”

She also has an interest in the sculptural and psychoacoustic aspects of sound. “It's so nice to have this really, really wide sound happening and then just being able to pull it down to a pinpoint . . . the sounds are choreographed,” she said. She is intrigued about the ways sound can shape the mind.

I always talk about trying to take the listeners on a journey,” she said. “Where they kind of . . . become one with the sound. Where it becomes a part of them and how they experience it from the inside out.

Payne's body of work also includes installations and collaborations with dancers and visual artists. One of her key albums, Crystal (1986), was an early exploration of art and technology, incorporating handmade videos of crystals growing under a microscope and data of solar winds provided by one of NASA’s top physicists, the late Fred Scarf.

To accompany the title track “Crystal,” she made her own footage of crystals growing in real time. “I was using my dad's medical microscope,” she recalls. She procured chemicals for the science experiment from a local company and painstakingly videotaped the crystals forming under a microscope. “That was really complex to do and that took a long, long time,” she says.

The notes on the back cover of the album, written by Payne, describe every track in intensive technical detail. “‘Solar Wind’ (1983) is an electronic piece based on synthesized audio representations of bow shock interactions of Saturn and Venus with the solar wind observed by Voyager, Voyager 2 and the Pioneer Venus Orbiter,” she writes.

Her elaborate notes are reminiscent of the essays on Brian Eno’s ambient albums in the 1970s and 1980s; Eno would also often use the back cover of the LP to write long explanations of what he was trying to accomplish. On the back of the 1975 album Discreet Music, for instance, he showed diagrams of his tape delay system and also provided a detailed explanation.

Many of Payne’s albums and track titles reference science and scientific concepts. Her album Arctic Winds, from 2010, includes pieces with names like “Fluid Dynamics” and “Glassy Metals.” “I love science,” she said. “I have a fascination with science and I have very limited ability in understanding science,” she said. “But it sort of creeps in, and I love these kinds of concepts and titles and stuff, so they're going to creep into my music one way or the other.”

Payne’s enduring legacy is not just through her own unique compositions; it is also through education. She co-led the Mills Center for Contemporary Music for many years, a descendant in many ways to the San Francisco Tape Music Center. In her many years of teaching, Payne has inspired several generations of composers and sound artists to investigate the potential of electronic music. “She dissolved my self doubt and demystified analog electronics,” says her former student and teaching assistant Marielle Jakobsons, a composer and musician in bands including Date Palms and Saariselka. Another former student, the composer, musician and producer Chuck Johnson, remembers Payne’s patience. “As a teacher, she is extremely generous with her time,” he says. “She really listened closely to whatever students brought to her, and she has an ear for detail – and a gentle manner of providing critique – that is exceptional.” Payne’s impact will continue to resonate into the music of the future.

About The Author

___________

Geeta Dayal is an arts critic and journalist based in Los Angeles who has covered experimental music for the New York Times, The Guardian, Rolling Stone, Wired, NPR, Slate, Artforum, and many other publications. She is the author of Another Green World, a book on Brian Eno, and is at work on a new book about music.